Here we stand in the shadow of two legendary 24 hour racing events, the 24 Hours of Le Mans and the Nürburgring 24, both delayed from midsummer to early fall in the wake of the global coronavirus pandemic. A longtime motorsport fanatic, I find myself sitting in the relative comfort of my living room couch at three in the morning — a little tired and a little wired from a pack of tropical Red Bull — dreaming of a day when these endurance races will be contested by ultrafast battery-electric machines.

Electric race cars are capable of prodigious speed, as proved by Volkswagen’s ID. R race car, among others. But the technology doesn’t yet exist to allow EVs to compete on a level playing field with, say, Toyota’s hybrid TS050 LMP1 racer. It might be possible to create a prototype electric car that can put down a similar qualifying lap time, but anything sufficiently quick wouldn’t be able to run an 11-lap (93-ish miles) stint. And even then, if any electric could make it that far that fast, the charging infrastructure and battery chemistry wouldn’t allow it to refuel in the sub-1 minute times that current prototypes can pack in a tank of fuel and change four tires.

It does very well to remember, however, that gasoline race cars weren’t always this way. While electric cars have technically been around since the late 1800s, fossil-fueled internal-combustion cars made them obsolete in rapid fashion and the technology atrophied while petroleum flourished. Mainstream reliable daily-drivable electric cars have only really been around for ten years or so. There’s still time for them to catch up, though. And to figure out how, we have to go back to the beginning of endurance racing, the roaring 1920s.

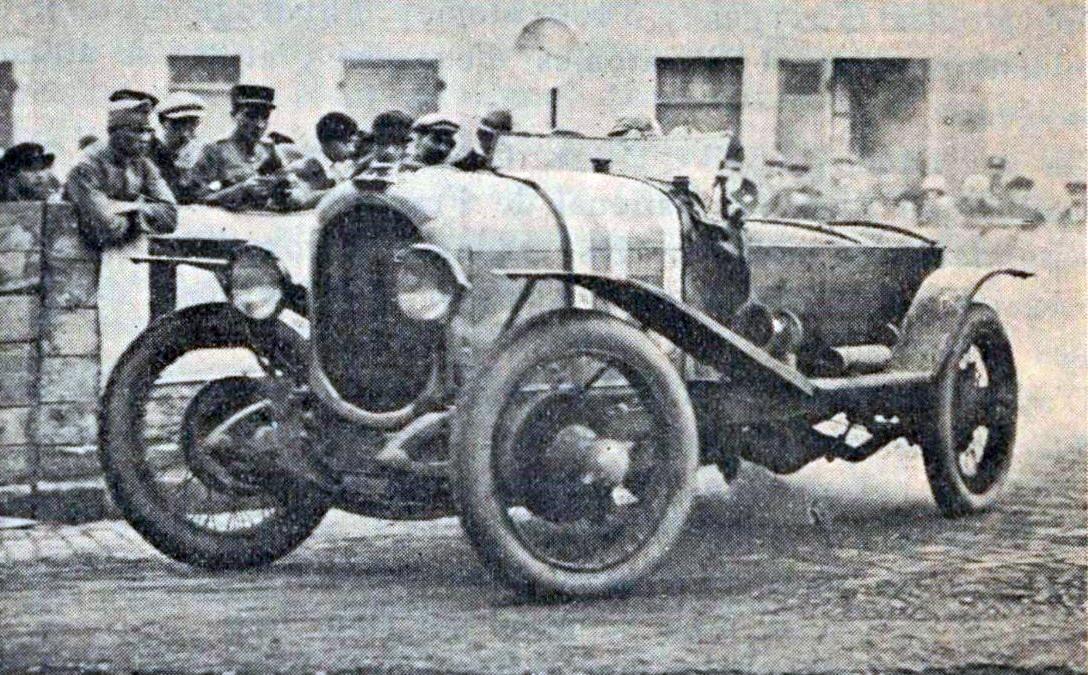

The first Le Mans 24 event took place in 1923, open only to mass-production four-seat touring cars and a small class of two-seat 1100cc sports machines. Two drivers would split the twice-around-the-clock campaign, and only those two were allowed to do work on the car, including topping up the fuel, oil, and coolant. The winning car, the 3-liter Chenard et Walcker pictured here, completed the race with an average speed of 57.20 miles per hour. Even in the twenties, cars were still largely experimental machines, and nobody knew just how fast a 24 hour event could be undertaken.

This event, then, was a proving grounds of sorts. In 2020, Le Mans is a test of the driver more than it is a test of the car. Basically for as long as I’ve been watching endurance events, the mantra has been that races are now a 24 hour sprint race, with little regard for the machine’s longevity. But that has come after 97 years of drivers beating on race cars, learning what breaks, and building them better next year. We need to apply that same logic to development of electric cars, battery technology, and charging devices.

EcoGP is a sanctioning body running a series of endurance races for electric cars around Europe to very little fanfare. The series pits largely stock Teslas and Renault Zoes against Kia Soul EVs, Volkswagen eGolfs, and others, running a standard charging infrastructure with everyone getting the same 22 kW of charge speed, mandating many teams to pit for 1-2 hours per stint. Obviously this method doesn’t allow something like a Porsche Taycan to take full advantage of its 270 kW DC fast charge abilities. That, I would argue, is where the EcoGP is failing.

In order to push charging and battery infrastructure, we need a new properly experimental electric alternative to early Le Mans. Open up charging to allow teams to pack as many electrons into their cars as they can. Open up regulations to allow teams to add a second battery stack if they so desire. Heck, we could make it an invitational to allow one-off projects like the EVSR team which put an electric motor into the belly of a Spec Racer Ford chassis. Let them push the boundaries of what can be done with electric power.

Mark my words, if we kick this thing off soon, it won’t take 97 years for electric racers to get to the level of competition that endurance racing has seen this year. What do you say? Are you ready to take the green flag on an electric endurance future?