Electric vehicle batteries require a host of special materials like cobalt, graphite and nickel, though lithium is arguably the most crucial. Securing commercially viable domestic sources of this all-important substance is paramount, and the state of Nevada will play a key role in meeting future needs.

“The question isn’t, ‘Is there lithium in the US and Canada?’” said Stephen Hanson, founder, CEO and president of ACME Lithium during an interview with EV Pulse. He explained this material absolutely is found here, we just haven’t exploited our reserves yet. Hanson said right now 95% of the world’s lithium comes from a handful of places: Argentina, Australia, Chile and China, with a huge share of this material — and other critical substances like cobalt, nickel sulfate and manganese — being processed or refined in the populous Asian country. For myriad reasons, this situation could lead to serious supply issues in the future.

SEE ALSO: 2023 Honda Accord teased, set to debut next month

According to the National Blueprint for Lithium Batteries developed by the Federal Consortium for Advanced Batteries (FCAB), “Maintaining and expanding lithium cell and battery manufacturing capability here in the US — as well as in allied and partner countries — is critical to US national security and is essential to developing resilient defense supply chains not under threat from near-peer adversaries.”

To help establish a reliable local supply, Hanson founded ACME Lithium in October 2020. Before jumping headlong into the lithium trade, he’s worked on a host of other resource-related projects around the world for 30 years. Quickly moving forward, “We made our first lithium discovery in July,” Hanson said, near Silver Peak in Clayton Valley, Nevada. This is right next door to the only commercial producer of this material in the US, which is operated by Ioneer, a large Australian firm that’s signed supply deals with Ford, Panasonic and Toyota.

The lithium Hanson’s startup company is hoping to harvest comes from liquid, “[A] brine that is found in aquifers.” He explained, this is accessed by basically drilling a well and pumping the lithium-laced salt water out of the ground. Additional work and testing will be required, but he hopes within the next 12 months they can determine if this lithium source is commercially viable.

To the west of their flagship Clayton Valley project, Hanson said they’re aiming to start drilling in Fish Lake Valley, Nevada sometime next year. Lithium has already been discovered on the surface at this location, so it shows commercial promise. Aside from the presence of this vital battery material, “Nevada is one of the best mining jurisdictions in the world,” Hanson said. The state has a great transportation network and no shortage of talented people. Also, while summers are hot, the climate is amenable to mining because, “It’s not in the arctic, it’s not in the jungle.”

MORE MUST-READ NEWS: GKN’s new internally cooled electric motor is an EV gamechanger

In addition to its operations in Nevada, Hanson said they’re also exploring lithium sources in colder, snowier Canada. “So, we’ve got three projects in Manitoba, in and around the Tanco (Tantalum Mining Corporation of Canada Ltd.) mine,” which is near the Ontario border and should be the only lithium-producing location in all of Canada. He expects to start drilling in Manitoba sometime in the fourth quarter of 2022, again, with the goal of producing economically viable quantities of lithium.

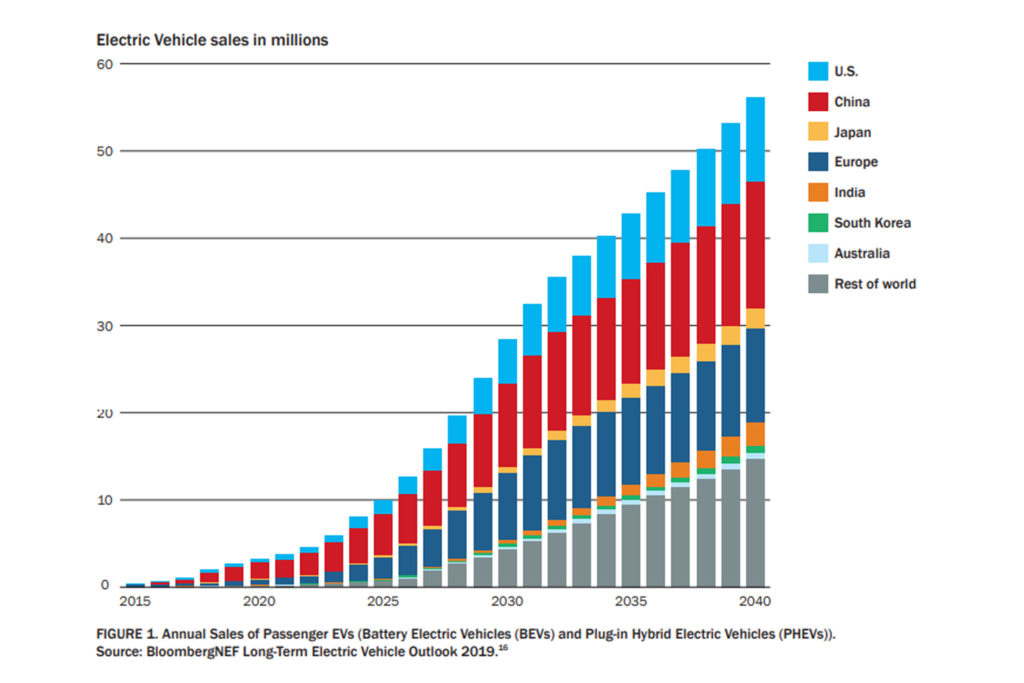

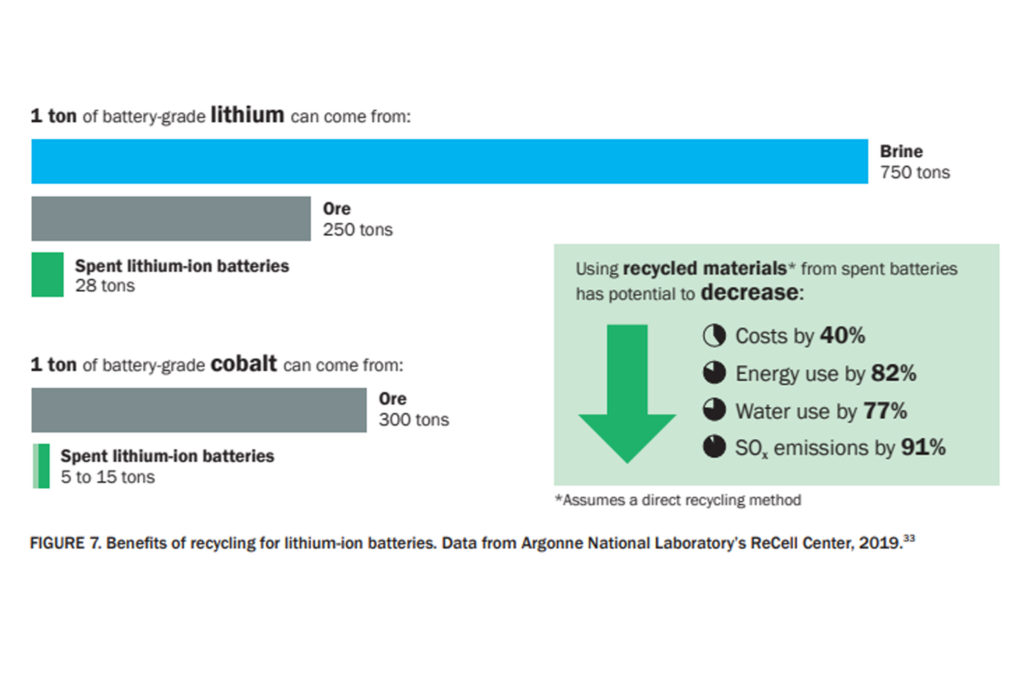

ACME Lithium was only founded two years ago, yet the company is pushing ahead because there’s real urgency to this work. According to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, a firm that provides information about and pricing data for critical materials, particularly those used in batteries and electric vehicles, “At least 384 new mines for graphite, lithium, nickel and cobalt are required to meet demand by 2035.” If battery recycling is factored in, that could drop to 336, though it’s still an astronomical number.

Looking solely at lithium, Benchmark Mineral Intelligence projects 74 new mines will have to open by 2035 to meet future needs. Assuming battery recycling advances in the coming years, 59 mines would have to be established, which, again, is a huge number, especially when you consider it takes untold millions of dollars and at least five years to get a mine up and running.

As automakers continue to electrify their vehicle lineups, the need for lithium carbonate is only going to grow. Hanson said it takes between 1 and 5 kilograms of this material to build a hybrid vehicle, 10 to 20 kg are needed for a plug-in hybrid and pure EVs take anywhere from 20 to 100 kg of the stuff. Lithium may not be a traditional precious metal like gold or platinum, but it certainly is a critical material, one that’s getting more and more valuable each day. As a commodity, Hanson said the price of lithium has gone up about 500% in the last year and there are concerns it will always be scarce. Based on what he hears from suppliers and investment firms, “The belief is we do not have enough lithium.”

As reported in the National Blueprint for Lithium Batteries, “The worldwide lithium-battery market is expected to grow by a factor of 5 to 10 in the next decade,” which will put enormous pressure on suppliers to ramp up existing production or tap new sources of lithium.

Echoing these concerns, when it comes to electric vehicle adoption rates in the coming years, Andrew Farry, general manager of business strategy at Tanaka Precious Metals told EV Pulse, “These are very ambitious road maps … And I think a lot of the projections are way off.” When it comes to other materials like cobalt, manganese and even something as ordinary as copper, “You’re going to have a bottleneck,” he added.

REVOLUTIONARY TECH: Breakthrough recycling process for lithium-ion batteries is clean, quick and economically viable

Tanaka Precious Metals deals heavily with automotive catalytic converters, which contain palladium, platinum and rhodium. For decades, the company has played an important role in recycling these emissions-control devices, though their business is changing. Farry explained, as electric vehicles become more popular, the need for oxygen sensors and catalytic converters will go down, but there are other opportunities with computer chips and batteries. “You’re going to have a lot more wiring harnesses, you’re going to use a lot more copper,” he added.

Of course, it’s not just EVs that require lithium. Smartphones, power tools, toys, computers, aircraft and military hardware all run on this hard-to-come-by material. But Hanson also said, “Probably the biggest use of lithium is going to be for grid storage,” to help bolster our electrical networks. “It’s a massive area that doesn’t get talked about enough,” he added.

Going forward, Hanson said, “Our goal is to determine whether we have an economic resource,” to focus on what has been “… a crisis in North America for domestic supply.” He also explained, ACME Lithium won’t necessarily get into the refining business, even if their goal is to ultimately sell lithium to battery manufacturers. To achieve this, Hanson said he hopes to form joint-venture partnerships with larger companies that specialize in refining, which, not surprisingly, comes with a host of other challenges

One way lithium is extracted from brine is by filling large ponds. As the water slowly evaporates, dissolved minerals gradually concentrate. Unfortunately, this process requires a lot of space and is slow, potentially requiring years before lithium can be harvested. Luckily, Hanson said a better option has been developed. “In DLE (direct lithium extraction), you’re actually pumping the brine into a plant and extracting the lithium in a direct process,” one that uses special membranes to filter the material out. This has a drastically smaller footprint, requires lower capital investment and is way less damaging to the environment. Companies like EnergyX and Lilac are working on DLE to improve the refining process.

When it comes to lithium production Hanson said, “The United States and Canada are far behind the rest of the world.” Hopefully ACME Lithium’s sites in Nevada and Manitoba prove to be commercially viable, able to help meet ever-growing demand for this critical material.