Whether it’s gold filaments in computer chip bonding wires, control switches containing silver alloys or catalytic converters loaded with palladium, platinum and rhodium, modern vehicles contain a range of precious metals. But as technology advances, the materials used in cars and trucks are changing dramatically.

As more and more electric vehicles hit the world’s roadways, “You’re going to have a lot more wiring harnesses, you’re going to use a lot more copper,” said Andrew Farry in an interview with EV Pulse. He’s the general manager of business strategy at Tanaka Precious Metals. “For us, it’s kind of a game shift,” he added.

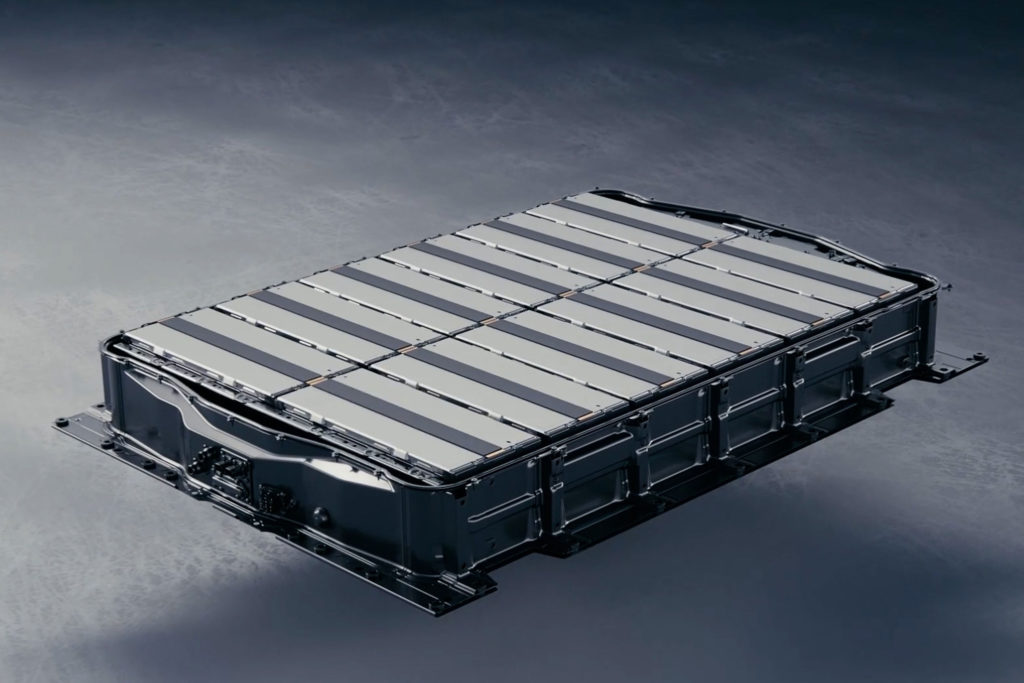

Electric vehicles have neither catalytic converters nor oxygen sensors, major emissions-control components that require precious metals to function. Instead, cobalt, lithium and manganese are materials that will be in huge demand — and likely short supply — in the coming years.

A Japanese firm, Tanaka Precious Metals has been in business since 1885. As the company’s name suggests, it deals with highly valuable metals, elements with countless industrial applications, though the firm also produces coins and internationally recognized bullion for investment purposes, and even sells products directly to consumers through retail jewelry stores. “There’s very little we’re not involved in,” said Farry.

SEE ALSO: Breakthrough recycling process for lithium-ion batteries is clean, quick and economically viable

What Tanaka does not trade in, however, are so-called rare-earth metals that are often used in electric motors, nor does the company deal with battery materials like cobalt, lithium and manganese. Even though Tanaka’s focus is on traditional precious metals, Farry said they closely monitor the rest of the industry.

Automakers and governments alike are pushing electric vehicles in a huge, and quite possibly unrealistic way. For EV adoption, “These are very ambitious road maps,” said Farry, “And I think a lot of the projections are way off.”

Metals like lithium and cobalt are of concern these days, with stories about price hikes or ethical issues making headlines, but Farry explained we may not even have enough copper in the ground to meet future demand. EVs may have more complex wiring harnesses than combustion-powered cars and trucks, but an even bigger concern is how much copper is needed to expand electrical grids in the coming decades to support all the battery-powered vehicles that are in the works. “Do we have enough known reserves … to meet some of these road maps?” Farry asked. The transmission wires used to move electricity from solar arrays in unpopulated areas or from offshore wind farms back to land, for instance, require vast quantities of copper. As green energy projects are expanded, more and more of this metal will be needed.

In an email, Farry said purchasing managers at automakers, supplier companies and battery manufacturers will be fretting over how to get the metals they need, where these materials will come from and how they can secure long-term contracts. “I foresee that leaders of that industry will be tearing their hair out for the next 10 years figuring out how they will combat this. There is only a certain amount of underground and overground supplies, and they will run out,” Farry added ominously. “There will be a shortage of material.”

READ THIS: Nevada could become a new powerhouse source of lithium for EV batteries

Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, a company that provides analysis and pricing data for critical materials projects that nearly 400 new mines will have to open globally by the year 2035 to meet demand for materials like cobalt, graphite, lithium and nickel. The recycling of these items can reduce the number of mines needed, but not by much.

Beyond finding new sources of critical materials, obtaining commercial quantities of them is not usually an ecologically friendly proposition. There are noxious mine tailings to contend with and the carbon footprints associated with extracting and refining are massive. And then there’s the monetary price tag. Farry said it costs millions of dollars — or more — and up to 25 years to get a new mine fully up and running. Unfortunately, there’s no silver bullet, no easy answer to cleaning up transportation.

Tanaka doesn’t trade in battery materials or rare-earth metals, but one way it can help the electric vehicle revolution is through its contributions to the solar panel industry. Via email Farry noted, “We will be involved in providing silver-based metals for that industry. We may see ‘flexible’ solar panels coming out over the next couple years as one of the most promising developments in solar technology.”

Beyond this, Tanaka has also been involved in the development of hydrogen fuel cells for more than 30 years. This propulsion technology is complimentary to electric vehicles and often scales better to larger applications such as over-the-road trucks.

The electric vehicle revolution is well underway, though there’s a long way to go before the majority of new cars and trucks sold are battery powered. EVs promise to make the future a greener, cleaner place, but shortages of critical materials and other supply bottlenecks could seriously impede the production of EVs.