The 2050 Decarbonization Road Map released by the Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs has received a lot of press since it was introduced late in December, but the details of the plan — especially the sections focused on transportation — still remain murky. Here’s a look at the background and the ways in which the 2050 Decarbonization Roadmap is long on initiative, but short on particulars.

The 2050 Decarbonization Roadmap

When the Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs announced the 2050 Decarbonization Roadmap in December of 2020, it took a lot of industry and policymaking observers by surprise.

In summary, the Roadmap is focused on three distinct categories of greenhouse gas emitters:

- Energy Supply

- Transportation

- Buildings

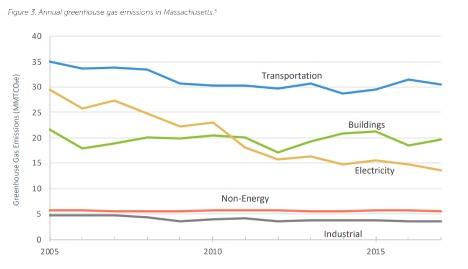

But by far, the lion’s share of the attention went to Transportation, which represents approximately 30 million metric tons of CO2 emissions (MMTCO2e) every year.

To achieve the goal of complete decarbonization by 2050, the Roadmap sets out the following strategy for the transportation sector: “Cars, trucks and buses are emissions-free and mostly electric: zero carbon fuels help power the rest of the transportation system,” as well as “A healthy public transit system, bike lanes, sidewalks, and transit-oriented development” to complement vehicle electrification.

According to the roadmap, 27% of the state’s annual emissions come from the light duty vehicles that Massachusetts residents drive every year. “By 2050, emissions from light duty vehicles will need to be reduced to near zero,” according to the Roadmap. “The primary strategy to reduce light duty transportation emissions is switching from fossil-fueled vehicles to zero emissions vehicles,” by 2035.

“Given the expected pace of new vehicle sales, the near term need to achieve significant emissions reductions, and the less-than-15 year average lifetime of most light duty vehicles, it is critical that this transformation accelerate to scale as soon as possible,” the Roadmap reads.

“Switching from fossil fuel internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs) to zero emission vehicles (ZEVs) represents the primary strategy for reducing emissions from the light duty transportation sector to the near-zero levels required for achieving Net Zero emissions statewide,” the Roadmap states.

The Field of Dreams strategy

There’s one paragraph in the Roadmap that addresses the significant roadblock to implementation:

The current pace of EV adoption in the Commonwealth lags the pace necessary to achieve interim decarbonization targets compliant with the GWSA. Without market intervention, fewer than 500,000 vehicles on the road are projected to be electrified by 2030. In contrast, reducing emissions 45% below 1990 levels by 2030 would require that about 1 million of the 5.5 million LDVs projected to be registered in the Commonwealth in 2030 be ZEVs.

The adoption in Massachusetts, though, is lagging in spite of market intervention. This isn’t the first time that Massachusetts has signed on to a Memorandum of Understanding with the California, and it’s not the first time that it’s developed an initiative that has struggled to set and meet achievable goals.

The first time was in 2015. Four New England states — Connecticut, Maine, Vermont and Massachusetts — signed a Memorandum of Understanding, which adopted California’s Zero Emission Vehicle mandate. The goal of the plan was clear: by 2025, 15 percent of the fleet of new vehicles sold in those states would be Zero Emissions Vehicles. That translated to approximately one in seven new cars sold in those states.

Massachusetts developed an Implementation Task Force that was charged with:

- Promoting the availability of ZEVs

- Providing customer incentives to purchase

- Converting the fleet of vehicles driven by public entities to ZEVs

- Encouraging private fleets to convert to ZEVs

- Promoting workplace charging

- Promoting ZEV infrastructure

- Providing clear and accurate signage to direct ZEV users to charging stations

- Removing barriers to ZEV charging and fueling stations

- Promoting access and to the plug-in electric charging network

- Removing barriers to the retail sale of electricity and hydrogen as transportation fuels

- Tracking and reporting progress toward the goal of 330,000 ZEVs on Massachusetts roadways by 2025

Since 2015, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts provided alternative fuel and infrastructure grants, allowed for a ZEV emissions inspection waiver, provided plug-in EV rebates up to $2,500, and delivered workplace EV Supply Equipment grants, along with incentives like toll waivers on the Mass Turnpike, the ability for ZEVs to use high-occupancy vehicle lanes, and even preferred parking at Logan Airport.

But the struggles to reach that goal were evident almost immediately. According to the Electrification Coalition, Massachusetts ranked fourth in terms of purchase incentives, but posted a “middling score” on infrastructure. As a result, between 2010 and 2017, Massachusetts had only registered 13,834 ZEVs, statewide, or 1.35% of the entire new vehicle fleet, well short of the goal the plan set for new EV adoption PER YEAR, let alone over a seven-year period.

The numbers have grown since 2017, but not in the kind of numbers that get Massachusetts anywhere close to 15% EV adoption in four years. According to Massachusetts Representative Carolyn Dykema (D – 8th Middlesex District), “The MOR-EV program has issued close to 18,000 rebates for electric vehicles since its implementation in 2014, and the legislature re-funded the program using Regional Greenhouse Gas funds in December 2019, providing up to $54 million over the next two years. Further, the program was expanded to allow commercial and nonprofit fleet vehicles to utilize the rebates in June 2020.”

Grants are a huge part of the motivation to get Massachusetts consumers to make the switch. “Last week, the Massachusetts Electric Vehicle Incentive Program (EVIP) opened applications for an additional $4 million in grants to support electric vehicle charging infrastructure to support both public and private efforts to install EV charging stations,” Rep. Dykema’s office noted. “These programs will be critical since municipalities and the private sector will be key partners in achieving the new law’s ambitious goals. Programs like these will help to accelerate the EV market, which has already seen improvements to cost and reliability in the past decade.”

EV sales have definitely picked up. 2020 was a bad year for car sales in general, but EV rebates applied for in the 2020 calendar year actually increased over 2019, even as the price of gasoline and insurance fell. Yet, according to Massachusetts Offers Rebates for Electric Vehicles – a program funded by the Massachusetts Department of Energy Resources – for the entire year of 2020, only 2,759 Massachusetts residents took advantage of EV rebates in 2020.

There’s little in the Roadmap that addresses this reality, and instead it suggests that as the industry builds more EVs, then the citizenry of Massachusetts will come. But that hasn’t happened, at least at the scale required to get to the levels the Roadmap requires by 2035.

When Massachusetts signed on to that Memorandum of Understanding, the field of vehicles was limited at best. There were only eight electric vehicles on the market. There were only seven plug-in hybrids, and just one hydrogen-powered vehicle.

Six years later, the field of EVs has increased dramatically. There are 21 EVs from major manufacturers available for the 2021 model year. Plug-in hybrids represented an even bigger leap, with 30 vehicles available by the end of 2020.

According to the Auto Alliance, in 2020, 96.15% of vehicles sold in Massachusetts were powered by ICEs. Despite the field of vehicles growing exponentially, just 2.03% of vehicles sold in 2020 were hybrids, 0.18% were EVs and 0.21% were plug-in hybrids. That’s in stark contrast to California, which has managed to convert about 5% of its new vehicle fleet to ZEVs every year.

Infrastructure remains a significant hurdle. Today, there are 3,194 electric charging outlets available in the state, but just 949 of those are public. In a 10 mile radius of where this article is being written, there are exactly 10 public charging stations, and the bulk of those are at town halls, primarily for the purpose of charging EVs leased by the town. (There’s one hydrogen fueling station in the state, and it’s not available for retail use.)

The housing realities in Massachusetts are also an impediment. Only 62% of Massachusetts residents own a home. Of those, just 52% of Massachusetts residents own a single-family, detached home where installing a charger has no limitations. 43% of Massachusetts residents live in housing with two or more attached units, making the installation of a charger not impossible, but that much more challenging.

The Commonwealth is hoping to address that particular issue with funds from an unlikely source: Volkswagen. “The MassEVIP program continues to provide grants specifically for public and private charging infrastructure and just opened up a new round of grants with funds from the Volkswagen settlement last week,” Rep. Dykema says. “A subcategory within this program is specifically dedicated to workplace, multi-unit dwelling and fleet charging stations.”

Yet, the primary infrastructure will continue to be private, via Level 2 chargers installed at home. “The availability of residential charging of electric vehicles was found to have a strong effect on EV uptake,” the Roadmap reads. “The majority of EV charging typically happens at home where most vehicles are parked overnight, providing a convenient and inexpensive way to ‘refuel’ EVs.”

There’s language in the Roadmap that seems to discourage the expectation that public charging stations are going to be that much more accessible: “Publicly accessible charging tends to occur throughout the day, potentially when other loads are also peaking, making managed charging more consequential. Public charging typically employs ‘fast chargers,’ which require higher voltages to facilitate faster charging times and subsequently higher levels of distribution infrastructure investment.”

92 pages of Roadmap: 5 pages of light duty vehicle plans

Considering the 2050 Decarbonization Roadmap pins the responsibility of the bulk of carbon emissions on transportation, and specifical light-duty vehicles, there’s precious little information in the Roadmap on how the Commonwealth gets to the final destination.

Just five pages cover the vehicles most Massachusetts residents drive every day, and more than a full page of that specifically addresses the drop in miles traveled during the height of the COVID lockdown, and how little that impacted the emissions of greenhouse gasses during that time.

The bulk of the plan is to continue funding incentives already in force to get consumers to purchase these vehicles. Massachusetts cycles through vehicles sooner than most other states, which is good news. On average, a vehicle in Massachusetts is 9.8 years old, two years newer than the national average. But the roadmap addresses what a massive challenge it is to turn that fleet over to an entirely new mode of transportation. Between now and 2035, when the Commonwealth expects 100% of new car sales to be ZEVs, most Massachusetts consumers will only buy two new vehicles. That’s just two opportunities to get these consumers to adopt a completely new means of transportation.

The public transportation conundrum

A major portion of the roadmap focuses on getting riders out of their cars and onto public transportation. It’s key not only for emissions reduction, but for Boston’s notorious congestion, as well. If there was any positive to the COVID pandemic, it was that traffic into the city fell precipitously. But unfortunately, it’s almost all back. “Statewide total weekday daily vehicle miles traveled (VMT) dropped from over 200 million at the beginning of March 2020 to about 80 million when the stay at home order took effect two weeks later,” says Rep. Dykema. “It remained below 100 million until May, when it began to rise. At Phase 1 of the reopening, the VMT hit about 130 million, and as of today has rebounded to about 75% (150 million) of what it was before the pandemic.”

But if Massachusetts is going to rely on public transportation, it has to be healthy and reliable, and that’s been a major issue in the Boston area for almost a decade. The Commuter Rail is aging and anyone who has ridden the T’s Red Line knows that service outages are an almost daily occurrence. The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) recently saw service cuts in response to low ridership due to the pandemic, but Metro-West legislators, including Rep. Dykema, detailed concerns about the cuts. In response, “the MBTA responded with a modified proposal released in December reducing the scope of the cuts, and the Fiscal and Management Control Board (FMCB) committed to reviewing ridership in February/March 2021 as part of the FY22 budget process,” Rep. Dykema told us.

Then there are the trains: All of Massachusetts’ commuter rail trains are diesel-powered. They help account for 40% of all the greenhouse gases emitted by transportation sector vehicles. In 2019, the MBTA release the Rail Vision Study that hoped to address this in particular. “The MBTA’s Rail Vision Study in 2019 resulted in an ambitious slate of resolutions endorsed by the FMCB that propose to electrify the public transit system and increase service frequency,” says Rep. Dykema. The text of Resolution 1 states that “the system of the future will be largely electrified, be fully integrated in all aspects into the balance of the MBTA system and that last mile/first mile, increased parking access and other elements will be implemented as part of this program.”

That requires a major influx of money, and it’s money that the MBTA doesn’t have. Rep Dykema told us that while the MBTA did receive $800 million from the CARES Act, the MBTA still carries a $600 million deficit. There’s $250 million coming from the latest stimulus package, says Rep. Dykema, “But that money will largely be spent on capital investments and the MBTA does not anticipate major changes to its service plan as a result of that bill’s signing.”

We’re only weeks past the Roadmap’s announcement, so the hard work of converting the new vehicle fleet to ZEVs is just beginning. But the clock is ticking. 2035 is 14 years away. It’s not yet clear how the Commonwealth expects to get consumers all over the state — including the 33 percent of the population that lives west of Worcester — to buy into this ambitious endeavor.

Updated (8:30pm EST, 1/13/2021): Updated to add quotes from Rep. Dykema and also updated for clarity.