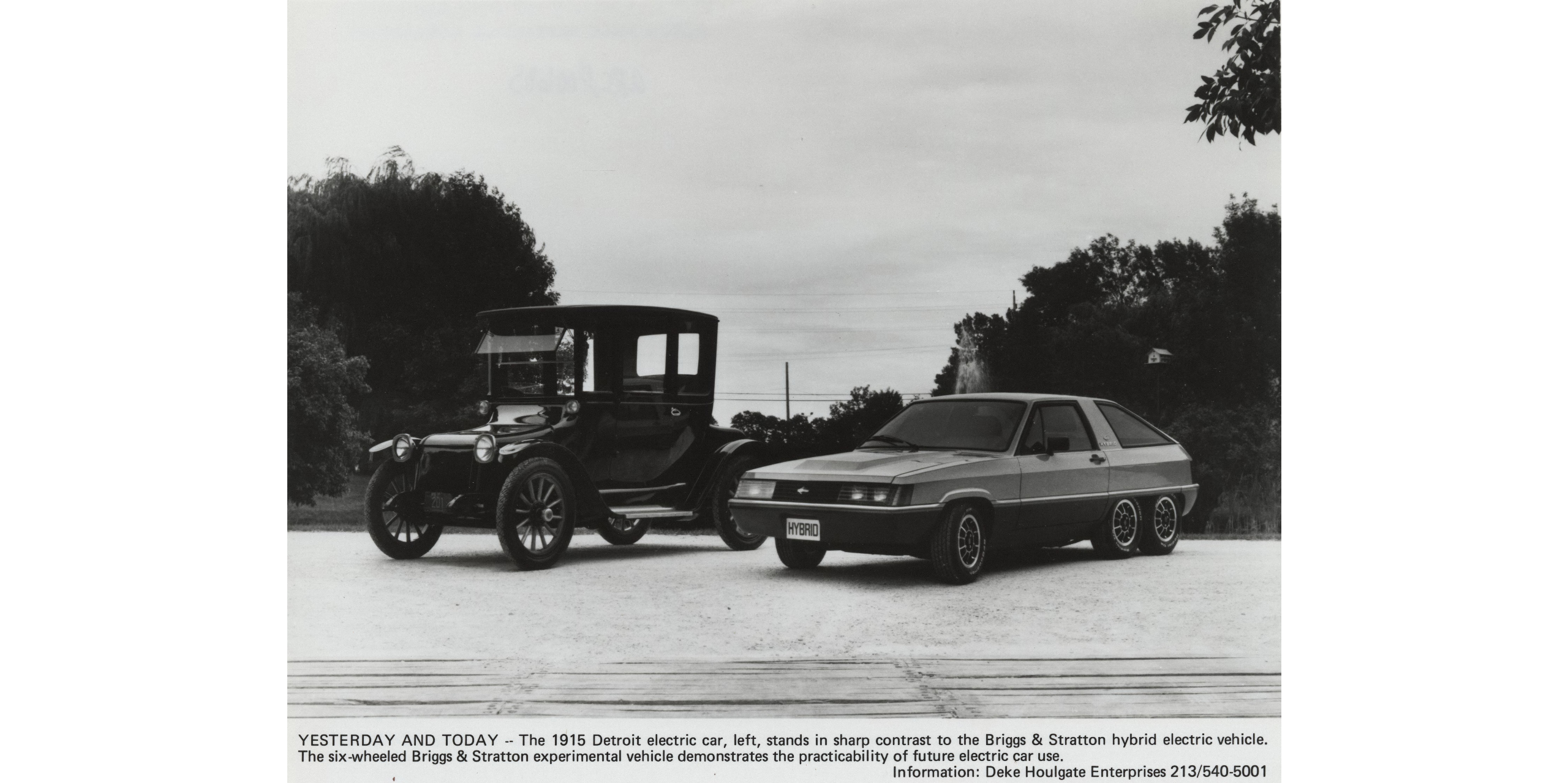

There’s a popular saying coined by author William Gibson that goes something like, “the future is already here, it’s just not evenly distributed.” So it goes with the history of hybrids and EVs, with early examples of what most think of as a modern phenomenon stretching back decades to the deep, dark clutches of the Malaise Era.

It makes a lot of sense that the 1970s were the kickoff point for electric vehicle technology. In the face of multiple energy shocks that saw America’s dependency on oil imports underscored by fuel rationing and soaring gas prices, the desire to look for an alternative to the status quo was strong.

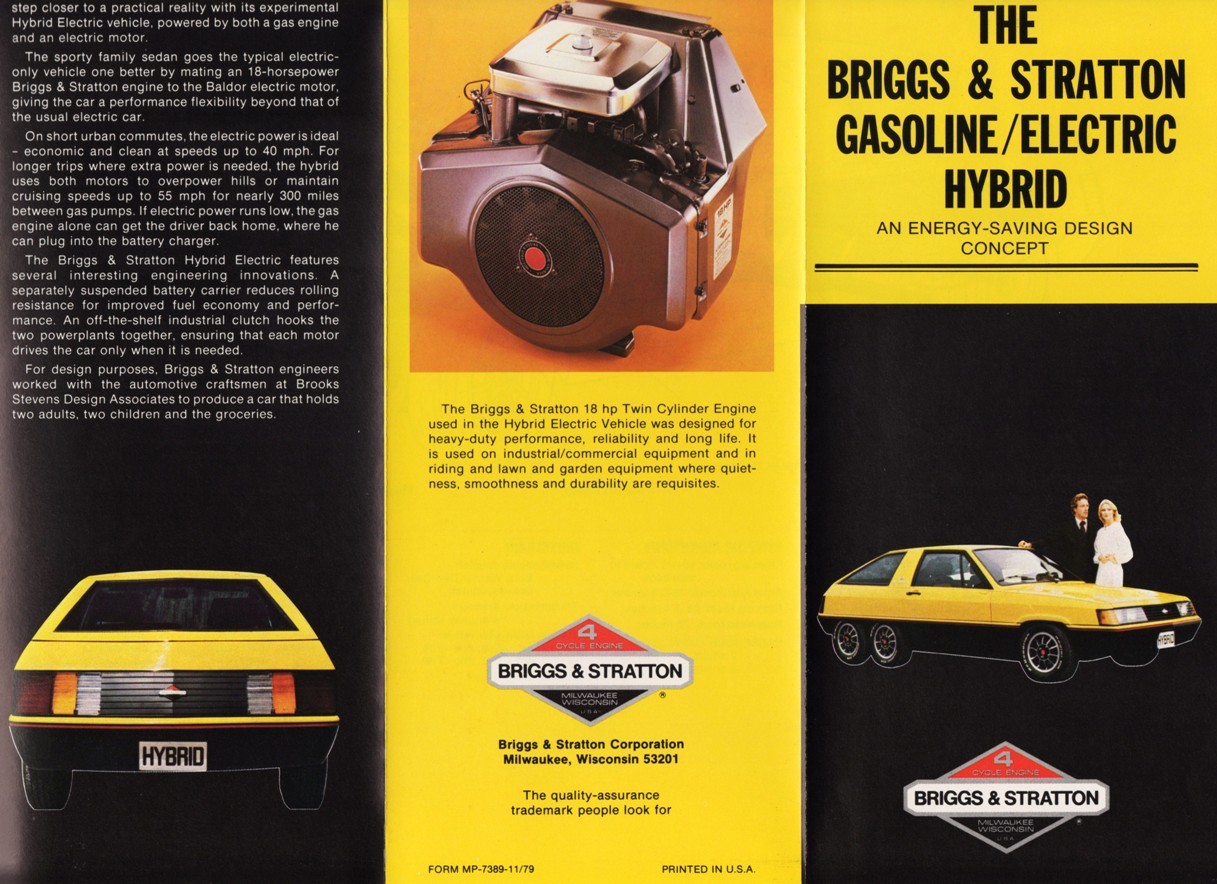

By the same token, so seismic were the shifts in U.S. energy policy that a number of players from well outside the automotive mainstream were intrigued by the opportunity to dip their corporate toes in a potentially lucrative new market. It was here that longtime small engine builder Briggs & Stratton saw an opportunity to not only raise its profile outside of the lawn mowers, Go-Karts, and generators it was known for building, but also make a statement about high tech transportation technologies that Detroit’s major players had largely ignored.

Why not think small (displacement)?

The roots of the project that became the Briggs & Stratton Hybrid were first planted in 1978 when the company became convinced that it could leverage its frugal, small-displacement engine lineup in the automotive space. It was an idea born at a time when the national speed limit had seen a legislated drop to 55 mph, cars were gradually shrinking in size from the worst of their 70s excess, and Japanese imports were beginning to convince Americans that bigger wasn’t always better, especially if you had to pay the feed bill.

With a suite of federal grants aimed at improving the current state of battery technology lurking in the background, Briggs & Stratton’s engineering brain trust came up with the idea marrying its existing small engine expertise with a little bit of electrical assistance. In 1978, the company began official development on what became the Briggs & Stratton Hybrid, a six-wheeled concept car that presaged many of the same design conceits that we now take for granted.

Sci-fi sextuple-feature

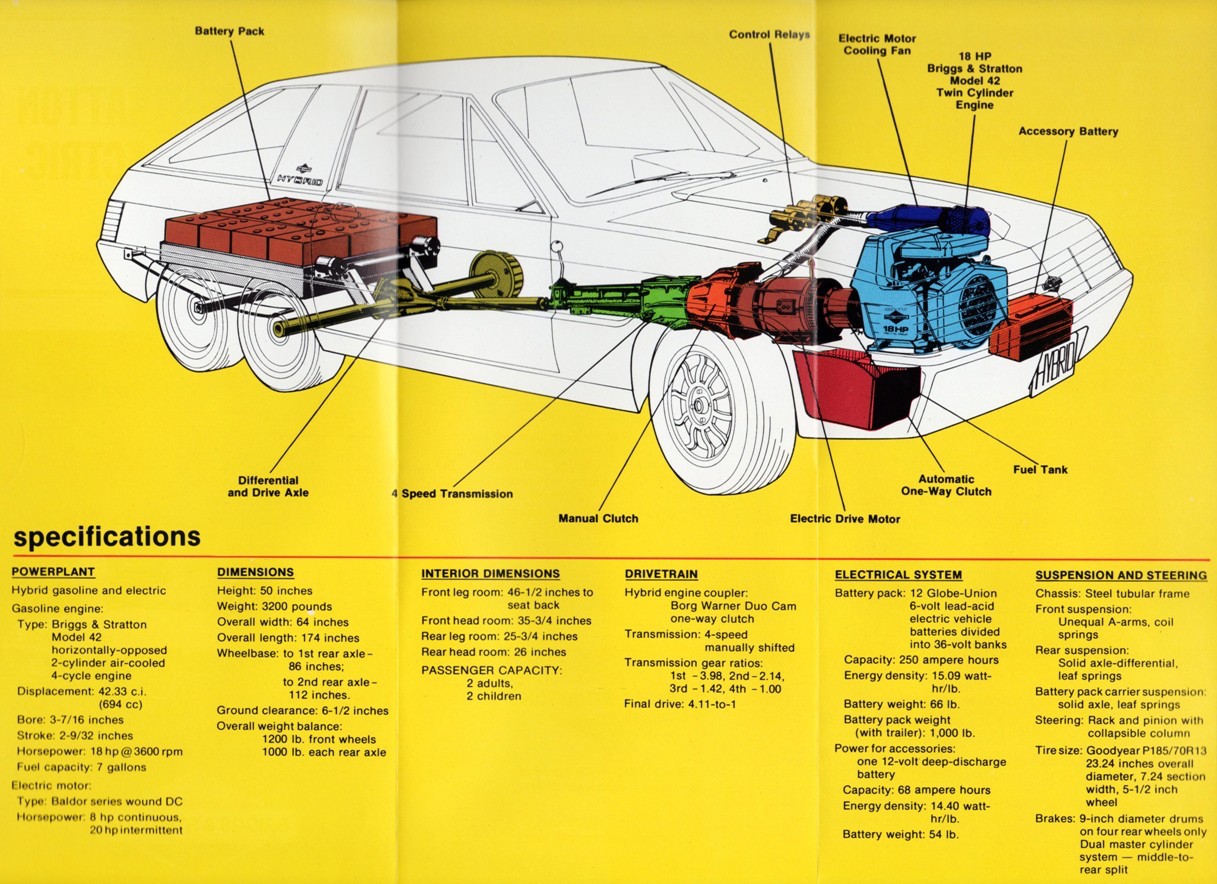

Wait a minute — six-wheeled? There’s a method to the madness of the B & S’s unusual axle count. Battery designs of the day were ungainly lead-acid arrangements, and the mass imposed by the Hybrid’s dozen 6-volt required a second axle to tag in and take the thousand pounds of weight. The solution came from an unlikely source: Montreal, Quebec’s Marathon Electric Car Company, which built an all-electric cargo van at the time (the C-360) whose chassis offered the axles and space needed to bring the Briggs & Stratton design to life.

Altogether, the vehicle weight in at 3,200 lbs., and it took roughly 8 hours to charge the batteries using household current. Interestingly, the rear tag axle was actually a structural component of the battery tray, and was intended to be snapped in and out for hot-swapping (although a second power pack was never built to demonstrate this capability).

The gas component of the Hybrid’s drivetrain consisted of a horizontally-opposed two-cylinder engine pulled from B & S’s industrial catalog. The air-cooled 668 cc design offered up a scant 18 horsepower, but it was matched with the 8 horsepower Baldor electric motor, with both sitting in front of the driver under the concept’s hood. Briggs & Stratton borrowed a 4-speed manual gearbox from the Ford Pinto, and the electric motor was connected by a Borg-Warner auto-clutch to the internal combustion unit. This allowed for the vehicle to be operated exclusively on either gas or electric power, or combine the two together.

Although much of the Hybrid was cobbled together from off-the-shelf components (given that Briggs & Stratton wasn’t itself an auto shop), the look of the vehicle was turned over to Kip Stevens, scion of design royalty Brooks Stevens (the man who had designed vehicles as diverse as the Jeep Wagoneer and the Oscar Mayer Wienermobile). It was a fitting bit of synergy between two Wisconsin-based industrial giants.

The company was eager to attract attention to the concept with a futuristic-looking profile, one that was certainly aided and abetted by its six-wheeled layout. Concealing the extra Pinto bits helping the Hybrid drive straight and true was a sleek hatchback body that looked as if it could theoretically enter production in short order. Hints of Volkswagen could be found in the A-pillar, while the interior was outfitted by Recaro.

Proof of concept

How did it drive? It depends on your perspective. Officially, the Briggs & Stratton Hybrid offered up to 45 miles of range on battery power alone, and with the gas engine pitching in it offered a healthy 30 miles per gallon (as tabulated using modern methods, with up to 50-mpg claimed by the company at the time). Both are impressive measures, especially given that none of technology used in the concept car was developed specifically to support a hybrid vehicle.

The actual experience behind the wheel called more for patience than exuberance. With both the electric and the gas engine working together, the vehicle could reach a top speed of 68 mph, which was the entire point — Briggs & Stratton had proved that it didn’t take a high cylinder count, or even triple-digit horsepower to ply modern roads — but it took nearly 30 seconds to get to freeway cruising speeds. If you stayed in gas mode, you could almost triple that time (with electric operation quicker than the 2-cylinder). This indicated that battery operation was better suited for city driving, with hybrid power necessary during longer journeys.

The Briggs & Stratton Hybrid concept cost a quarter of a million dollars to build, and when it was unveiled in 1980 there was no clear path forward for the vehicle. The company had no plans to put it into production, and it unfortunately was viewed more as an oddity by the major automotive concerns of the day rather than an inspiration. Recently brought back into driving condition for an episode of Jay Leno’s Garage, the Hybrid concept sits in the Briggs & Stratton archives as a shining example of a path not take until much, much later in our timeline.